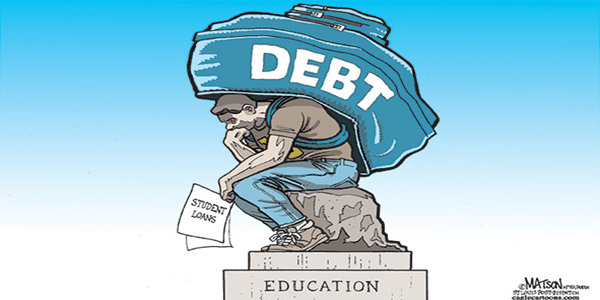

A few years ago I was a supporter of the online movement to forgive student loan debt to stimulate the economy. And, in many respects, I’m still a supporter of the concept. As the movement is beginning to gain some more momentum (though not enough for it to be implemented in some form, which is a shame), I thought that given my expansive experience in repaying student loan debt I’d offer just a brief commentary giving some of my thoughts on the issue.

To begin, if you really want to read up on this issue you should head over to the Forgive Student Loan Debt website – tons of information over there on the idea and concept. More recently, the New York Times commented on the concept of forgiving debt in a commentary posted to their website, which you can access by clicking here. The New York Times piece makes a good point about the downside of forgiving debt, in general, when it suggests:

To start, writing off debts would not necessarily increase economic growth. Every liability is also an asset, so while a dollar that is no longer required for debt repayment might add some cents to consumer spending, it is also a dollar cut out of a bank’s capital or of an investor’s net worth — subtracting from resources and confidence.

And write-offs big enough to change consumer behavior would probably be big enough to destabilize banks. The Federal Reserve or the government would need to help, presumably by injecting newly printed money as capital. Such government control is usually inefficient, and abundant printing of money increases the risk of uncontrolled inflation, which has its own way of making people feel poorer.

The issue of moral hazard also cannot be ignored. Much of the excess debt was incurred through irresponsible mortgage refinancing, which peaked in 2006 at $322 billion, representing 2.4 percent of G.D.P. The reckless use of houses as A.T.M.’s was a major factor in decapitalizing and destabilizing the American economy. Forgiving such debts will teach the wrong lesson: borrow in haste, repent never.

Okay. They’re right. I get it. Makes sense. But what about student loan debt? Does forgiving student loan debt make any difference in this equation? I think so.

Sure, I agree with the New York Times about the moral hazard issue and I would hate to see folks incur massive amounts of debt only to discharge that debt via bankruptcy a year after graduating. That wouldn’t be right. However, I would like to see a system that allows for some level of forgiveness for student loan debt after a certain period, time spent working at a certain job, or some other logical qualifier. The federal government has a program that like that right now where after working for a nonprofit organization or for the government for ten years, the balance of your student loan can be forgiven (the program is so much more complicated than that, but you can look it up if you want to know more about it).

Megan McArdle wrote a very good article in The Atlantic the other day about this issue. I think that my point of view is very much in like with Ms. McArdle’s thoughts. In her article, she writes:

By allowing students to shift forward the additional income that their degree will earn them, student loans have allowed universities to capture a huge portion of that future income stream–which really hurts those for whom that stream doesn’t materialize. Moreover, it allows students to make the sort of stupid choices that most 19-year-olds will make if they’re allowed. I don’t have a lot of patience for university administrators claiming that they just can’t possibly charge less than $25,000 for 15 hours a week worth of classes, but they do have one point: they build expensive new facilities and load on the services because students demand them, and threaten to go elsewhere if they can’t get them. Colleges look ever-more like four year resorts with a sideline in academic research.

If students actually had to earn the money to pay for that world-class fitness center, the 2,000 different clubs, and the off-campus apartment with the pizza parties, there would be a lot less of those things. And while I like both world class fitness centers, and apartments, they’re not the sort of thing that should be funded with borrowed money. If the degree caused pain now rather than pain later, they might also think harder about whether what they were studying was likely to deliver a solid return on that investment. I’m not faulting the students–the future is a pretty hazy concept when you’re eighteen. I’m just arguing that it’s not necessarily helping to enable them.

For me, this is the crux of the issue. I’ve been saying for a while that I really don’t like the social system we’ve built in this nation where we tell young people that their ideal life is to do well in high school, immediately go to college, and then begin working for the next 35 – 40 years of their lives. That’s not conducive to the type of futuristic, 21st Century society that we should be building. Yet, we’ve not only created this social ideal, but we’ve found a way to fund it in a manner that allows colleges and universities to make a ton of money! That’s not conducive to many things including increasing the value of a college degree in the workplace (which colleges should be concerned about) and increasing college graduates’ personal wealth (which all college graduates and their families should be concerned about). So, as the folks at the Forgive Student Loan Debt website can tell you – the system is clearly broken.

I’m not the type of person to throw the baby out with the bathwater, though. And it is in that mindset that I believe we shouldn’t forgive 100% of student loan debt. Instead, we need to fundamentally change the system for both current borrowers and future borrowers. For example, to address the concerns of those borrowers who currently have outstanding student loans and are struggling to repay them, we need to create truly flexible repayment programs. In other words, we don’t need to capitalize interest on loans that are in deferment – we need to eliminate the interest on those loans, period. For a private banker, that’s the epitome of a risky loan so I understand that this type of recommendation will likely create a culture shock at the local bank. However, if I’m the guy who runs the local bank, I’m more concerned about having my principal repaid – even if it’s over time – than having a loan go into default because the total burden was too much for the borrower.

And on the same note, if banks continue to want to fund student loans, then they need to do better underwriting to make sure that the person who takes out the loan can repay it once the time comes for repayment. But that’s a topic for another post entirely.

For future borrowers, I’d be in favor of a graduated borrowing schedule and a total student loan cap. I don’t know what number would work or what the system would look like in its final form, but I don’t see why we couldn’t form a program where students are allowed to borrow (for example) up to $10,000 during their Freshman year, $8,000 during their Sophomore year, $5,000 during their Junior year, and then $3,000 during their Senior year. In total, that’s $26,000 worth of student loan debt (which should also have flexible repayment options and a very low interest rate). Repaying that amount of student loan debt is totally reasonable. Plus, a graduated debt schedule might entice students who do not currently work to get a part-time job (or two) while in school. It would also encourage students to think twice about those stupid choices that Ms. McArdle references above.

What it comes down to is education about the system. In the current system or in a revised system, more people just need to understand the entire student loan industry before they choose to take out those loans. And I think we’d be hard pressed to try to force all of the knowledge into the heads of young people. Instead, we need to be sure that the parents and guardians are more aware of what the implications of these students loans are in the long-term and hope that they educate their kids about the possible outcomes. There are always going to be outlier situations, of course, where some folks get themselves in very deep debt. But if we – as a society – understand the issue better, we might be able to find a reasonable way out of this hole.

For me, though, I’m in favor of some form of forgiveness of student loan debt. I’d probably focus on eliminating the capitalized fees, interest, and penalties from the student loan balance first. Then, I’d try to encourage the expansion of the debt forgiveness program I referenced above. Again, we don’t need to eliminate the entire system – we just need to recognize that it is broken and begin working to really fix it – right now.